A note of optimism for today’s uncertain times

JohnOSullivanThe Budapest Times talks with expat resident John O’Sullivan, Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE), whose distinguished career as a conservative political commentator and journalist has included being speechwriter and adviser to Margaret Thatcher, vice-president and executive editor of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and, since 2014 when he moved to Budapest, founder and president of the Danube Institute, a think-tank specialising in international affairs, economics, politics, and culture.

I sense that Margaret Thatcher’s remarkable legacy as UK prime minister from 1979 to 1990 prevails wherever you are. At times she proceeds before me, as I too come from England and Hungarians in Budapest, particularly women, often talk about her. Interest in the “Iron Lady” remains strong regardless of critics. How do you define her?

Yes, Mrs. Thatcher remains of interest everywhere, in particular in Central and Eastern Europe because of her part in bringing an end to communism. Also, today’s Conservatives and economic entrepreneurs see her as a role model; and, finally, those in and out of politics who really got to know her during her time in office admire her. She was, of course, a very important influence in my own life. Remarkably, at our first meeting we had a big argument about education vouchers [a certificate of government funding for a student at a school chosen by the student or the student’s parents, usually for a particular period]. I was in favour of them; she was not in favour of them—not at least for many years. But we got on very well after that.

What I hadn’t known was that Prime Minister Thatcher respected those who were open, direct and honest with her. She thrived on argument and the cut and thrust of debate – getting to the point, examining the point and at times demolishing the point. It was her way of learning and making sure she understood her own case as well as the other person’s. I was very lucky to have worked with her at Downing Street, and later when she retired, to work again with her on her two volumes of memoirs. I was also an adviser to the Thatcher Foundation. These were all great experiences that in addition to being fun, also opened many doors later.

History will remember her favourably in international relations and as the most successful peacetime prime minister since 1945. Margaret Thatcher was not a populist, in the modern sense of the term; she was an English conservative with a strong belief in free enterprise and the free market. But there was also a nationalist vein in her thought and policies: she believed in the greatness of the British people and she instinctively hostile to the encroachments on UK sovereignty from Brussels. But both her free market ideas and her belief in Britain led her to fight battles against entrenched opponents like the miners and the Eurocrats. In that regard she was like Franklin Roosevelt, the strong-willed American president from 1933 to 1945 who led the US through the Great Depression, WWII and won a historic four terms in office. She altered British society very dramatically—and I think for the better as records now show—but she had to take fight hard to do such things as remove trade union privileges, defeat strikes, and contest a hostile Labour opposition party. As Roosevelt also found, it is not possible to fight these major battles and to be liked by everybody.

Please tell something about Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty during the 1980s that relates to the fall of communism.

I did not join RFE/RL until 2007, long after the Cold War had ended. But I recall that RFE/RL was a topic of controversy in Washington in the 1980s when there was nervousness on the Left that the two radios were in the grip of unrepresentative exiles, hostile to détente, and an obstacle to better East-West relations. Investigations were held into the radios, but they found almost all of the criticisms were baseless. RFE/RL emerged very well from this period. Ronald Reagan increased their budgets considerably, and their managements had long imposed high journalistic standards and maintained a very strong research department that was vital to serious scholarship into the Soviet Union and its systems. With the rise of Poland’s Solidarity in 1980 and later resistance movements in the Soviet bloc that followed, RFE/RL covered these developments with greater expertize than most Western media and delivered a very fine news service to those behind the Iron Curtain. When the Berlin Wall finally fell, critics from Washington and elsewhere had to admit that RFE/RL did a great job, one without bias incidentally, since such figures as cited by Czech president Vaclav Havel and Hungarian president József Antal, and later Polish foreign minister Radek Sikorski, said such things as that they owed their political education to RFERL.

After 1989 RFE/RL served as a kind of a school to new and aspiring journalists in the former communist countries who wanted to learn new modern-day methods and how to deliver news without propaganda. There are always certain risks media stations and journalists must take in order to do this. In the Cold War Soviet officials jammed our frequencies frequencies and threatened our reporters. A bomb went off at RFE/RL in Munich during the 1980s. In more recent times there was a news story in the Czech press that Saddam Hussein had sent agents into Prague to fire a rocket at RFE/RL. And today RFERL’s journalists continue to be detained under house arrest or imprisoned by regimes anxious to suppress stories of their corruption. One colleague of mine was imprisoned in Baku; another was murdered, apparently by Uzbek secret police. Historically RFERL has done, and continues to do, a great and necessary job of telling people the truth about their own societies and governments; and I admire my old colleagues without reserve for making such a good job of it. It was a privilege to work with them.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was a joyful time as it defined an end of an oppressive era. Unfortunately, there are now new emerging conflicts between modern-day democracies versus old-style leaderships, as with the case of Ukraine and Russia. Will Europe and NATO weather this storm, alongside Brexit, or do you think more walls, fences and perhaps further conflicts are on the horizon?

NATO will survive because it protects the independence and democratic rights of Europe and America. It is in the interest of all these countries, its members, to keep it going. Brexit will have no effect on this, despite any impact it may have on the EU. In short, Brexit will damage neither NATO nor Europe, and arguments to the contrary are largely scare-mongering by those who would like to reverse the result of the Brexi referendum. As for Mr. Trump, yes, he undoubtedly offers a challenge to the NATO status quo. But the entire American political system is committed to NATO as a national security interest of the US. When the new President evaluates this seriously in practice, I am sure he will see the necessity of maintaining it. And it may even be the case that what he is doing now may be fruitful to America. He is saying to the Europeans: “You cannot expect us to pick up such a large share of the tab for your own defence.” And as the threat mounted bv Mr. Putin develops—and we shouldn’t underestimateit—Trump’s argument gets more powerful. This may produce a better result with further defence spending in European countries as they can afford it.

There will be various bargaining chips between Trump and Putin. But what is clear: what Russia is doing today is not honestly sustainable. With their continued “interests” in Ukraine and Syria, alongside low oil prices and sanctions, money is fast dwindling from their economy, which may result in collapse. How do you view this very delicate, ongoing matter?

These problems are real. Russia is a small economy with falling revenues from its principal export and a massive military budget. There will have to be retrenchment somewhere—and that may include or cause a less aggressive foreign policy. I doubt there will be a collapse. But one can’t rule one out. Consider history: the Soviet Union was bankrupted by its decision to spend 40% or more of its GDP on military investment. And Russia’s over-expansionist foreign policy could produce a similar result by accident.

And for what? All this is needless. Neither today nor in the Cold War was there ever a serious threat to Russia from the West. Stalin and his successors conjured up a threat out of their own imagination and propaganda, and frightened many of their own people into believing it. But the Russian authorities have always known… the threat from the West was not true. And it isn’t today.

And if there is a threat, why do many of Russia’s leaders today have apartments in Paris? Go shopping in New York? Send their children to Oxford and Cambridge? This is not the same relationship as in the Cold War. If war did come, which I don’t think it will, it would come by accident and not by design, and that is what we have to guard very much against. But the anti-Westernism campaign the Kremlin is running is a mixture of absurdity, lying, and aggression.

Against it, I think the Ukrainian people have shown great courage and steadfastness in defending their own independence. This may not be clear to everybody but I think Mr. Putin made a geopolitical mistake of great importance when he began banning agricultural imports from Ukraine, which also led to the 2013 Euromaidan and breakdown of relations. The final truth is, he has lost Ukraine. He may have a small part of it which will be expensive and difficult to run. How long will this statelet in eastern Ukraine last? I don’t know. But I don’t think for long.

As a Brit living in Budapest I am troubled by Brexit, as local people often ask me “Why?”. Also I often go to Ukraine and meet many who really see the EU as a great hope and a way forward; so much so they are willing to risk their lives for such a privilege. While it would seem the UK has surpassed the EU and is now making slow, ambiguous efforts to pull out. With a significant rise of the right wing and a call to secure more borders, will a Brexit domino effect soon follow?

No I don’t think a domino effect will happen. Brexit is about the British leaving and nobody else. The British have no desire to persuade anyone else to leave; indeed, we remain happy for others to join the EU if that is what they wish. The significance of the EU for central Europe in the past—and for Ukraine today—is to symbolize an irreversible move from dictatorship to democracy and freedom. Such a move was not necessary for the British in the same way since we haven’t suffered occupation for more than 1000 year. In fact, we experienced the EU as a kind of gradual loss of liberty.

If you want to know why Britain is leaving, it is very simple: we want to be a self-governing democracy as we were throughout our long history. We have different legal and political institutions; they are less centralised and more local than in most of Europe. That is the kind of society we want to live in. Most Brits feel they are not comfortable in the institutions of the EU and that is why we do not want to stay in them. It may suit others but not us.

As for Ukraine, that is a very different matter. I am a strong supporter of Ukraine and its application to join the EU because that is what they want. It is clear they don’t want Russian rule; they don’t want a system in which their president is almost always a criminal; and they want to move forwards into a Europe that they see as a guarantee of a less oppressive system. Of course, their vision is probably too rosy. They will find themselves facing new laws from Brussels that they don’t much like. But their situation and opinions are different from those of the Brits. And I think they will adjust more happily than we Brits did in the forty years since 1975.

What are you working on at this moment?

I spend most of my time writing and editing the “Hungarian Review” magazine, as well as the American “National Review” paper and the Australian “Quadrant”. All cover the arts, news and current affairs, all are broadly conservative in tone and content, all can also be seen online, all are fine magazines, but they are all very different from each other too.

You originally come from Liverpool. Did you see The Beatles live at the Cavern Club?

I am an exact contemporary of The Beatles. I grew up at the same time as them. They turned out to be really impressive musicians and poets. -But no, my musical tastes have always been elsewhere with classical music, some jazz, and in particular the tradition of “The Great American Songbook” of songwritingfrom about 1890 to about 1960. Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Irving Berlin: they are the musical greats, not just from just a musical point of view but also lyrically. Their lyrics are modern poetry that at their best express the deepest feelings of the human heart, a tenderness and, at times, a witty and melancholy acceptance of how things are, much more so than the popular music of today. They even sound Hungarian to me at times.

Finally, what is best about Hungary?

That is a very hard question as there are so many good things. I came here first in 1971 and even then Hungary was the best country in the Eastern Bloc—the jolliest barracks in the socialist camp as people then said. The food is excellent, so is the wine. The British embassy tells me that Budapest is the sunniest capital in Europe. Hungarian music is wonderful; the town is rich in concerts, recitals, operetta, and opera, which I very much enjoy. The cost of living is low; the quality of living is high. And the Hungarians themselves are very pleasant people, likeable, amusing , with a vein of and very proud of their country. Hungary is one of the few places where the national anthem is sung passionately. Once you ask me to talk about Hungary’s virtues, it is hard for me to stop!

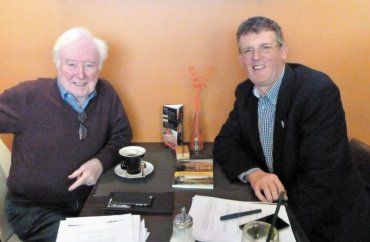

Alexander Stemp concludes: We could have continued but we rounded off our conversation on this cheerful note. I really sensed John O’Sullivan’s general optimism and mastery throughout our exchanges. He has obviously seen it all politically and has a forward-thinking mind that made me feel more assured the world is not going to end just yet, and that life still has a meaning and a purpose with much to offer, regardless of today’s often troubling news.

6. March 2017 - by Alexander Stemp in Interview

UA-Reporter.com